Working with Concrete

Working with Concrete

Through our work with new and existing buildings, we have often encountered concrete as a primary building material. Concrete is selected for use in buildings for different reasons and we’ve selected two very different projects to share how and why concrete can be used as more than just a structural material.

Working with Historic Concrete

Written by James Kirk, Associate at MICA.

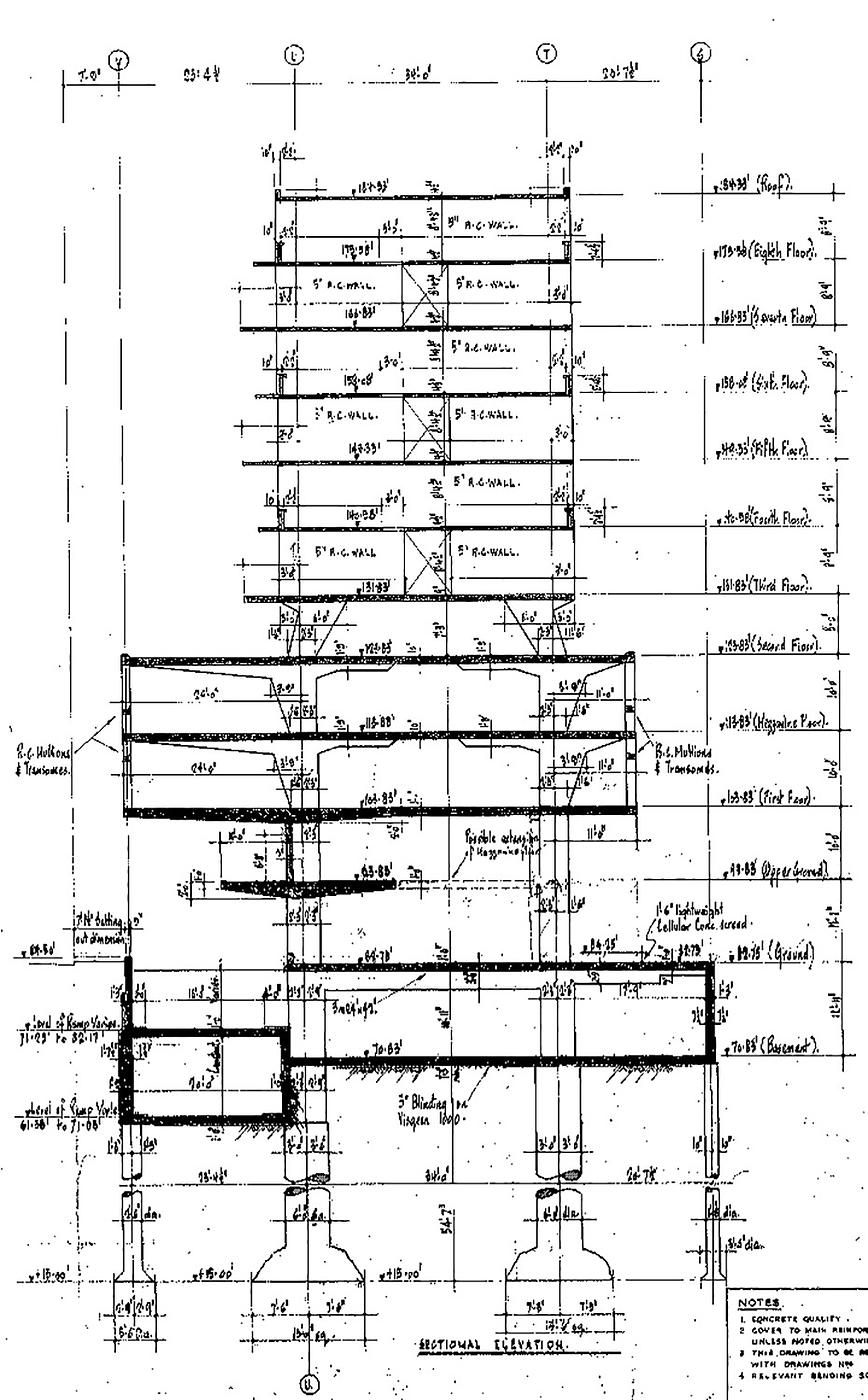

Our work at Centre Point involved considerable restoration, exposure and celebration of historic concrete finishes and structures. The original building, heritage listed in 1995 was completed in 1966 by Richard Seifert and Partners with Pell Frischmann.

The Centre Point complex is made up of four parts, each with a different character expressed through its use of concrete. The character of the tower is most strongly expressed through its white precast concrete ‘crocheted’ cladding units, repeating and tapering up to the 34th floor.

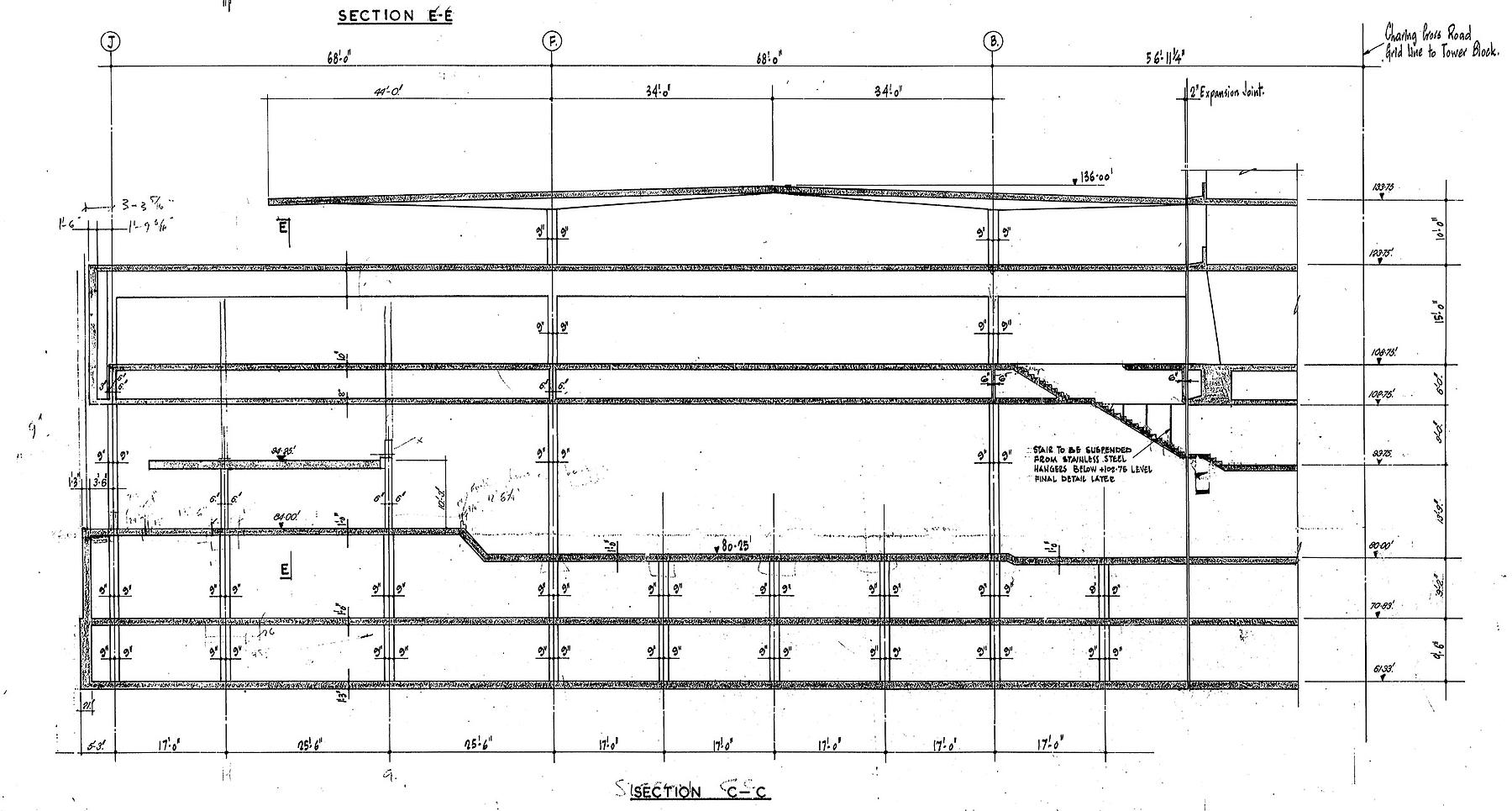

The bridge link is defined by its stacked post-tensioned concrete slabs at first and second floor levels set on sculptural columns, which allow the buses to drive under the building on St. Giles High Street. This remarkable structure is expressed externally through a huge corduroy or ribbed soffit highlighting the expanse of the span overhead.

Centre Point House, running perpendicular to New Oxford Street towards St Giles Church has a large sculptural brise-soleil facade, formed in reinforced concrete and clad with white terrazzite, chosen originally to match the colour of the facade units of the tower, but using a considerably cheaper finish which has required significant cleaning and restoration works.

Finally the new housing block facing the church which replaced the modernist pub originally on the site is clad with a white precast concrete facade embossed with a pattern based on a study of the geometric facades of the tower. We worked to restore each of the historic exterior finishes to the quality of their original specification after decades of exposure to one of London’s busiest areas, and we designed newly built parts to match the character and durability of the original.

The structural ingenuity of the original building places considerable technical constraints on any modifications, particularly in the bridge link. The concrete making up this part of the building performs both a sculptural and structural function. The original historic structure defines a strong horizontal composition using stacked ‘post tensioned’ (or PT) slabs. Post-tensioning the slab allows the concrete to span the large distance over St Giles High Street, and cantilever towards the tower, supported on just three bays of sculptural concrete columns. These columns express the structural ingenuity of the concrete above by barely touching the underside of the PT slabs, leaving large gaps between the column and the ribbed soffit. This allows the slab to flow over the columns, appearing to float effortlessly, although the concrete is working at its structural limit. The columns, oversized for their function, appear as sculptural elements within the streetscape, offering a generous addition to the public realm.

These remarkable elements have been preserved and restored in our changes, exposing and celebrating the existing structure with minimal alteration. Where non-structural walls interrupted the space at first and second floors, we have removed them to show-off the expanse of the original space, and expose the spectacular structural gymnastics achieved by the original building. This restores a grand, light filled hall with expansive views over a newly-created public square and up and down Oxford Street and New Oxford Street.

In Centre Point House, our work has been more structurally significant, including the removal of concrete slabs and floors. This has created an area of clerestory glazing high above the first floor expanding the space up over 7 metres to create a generous ceiling height and bringing in lots of natural light. We have carved out of the structure a set of expressive geometric concrete piers in bays which contribute to the cathedral-like space, revealed by our structural modifications, which celebrate the original sculptural concrete elements of the building in a new way.

These changes are made possible by an understanding of the original concrete structure and the design intentions of the original architect. In our new build projects, we are able to form these concepts from first principles, using concrete to help shape and sculpt space.

At the Customer Service Centre & Library in East Ham a ‘simple’ concrete frame takes on several roles.

Working with New Concrete

Written by Paul Mullin, Associate Director at MICA.

The contribution concrete would make was identified early on as a vehicle for “elegance and economy”. Concrete was considered as means to achieve multiple outcomes, a material which would contribute through the duration of construction process, without risk of losing quality through value engineering. It was also seen as an opportunity for the concrete finish and its resultant forms to become an active participant in the everyday use of the building.

The principal reasons for the selection of a concrete primary structure over alternatives, was the added value it gave to the project as a whole. We concluded that concrete could meet the objectives of a demanding client brief, whilst upholding the architectural intent: simplicity, coherence, robustness, and of elegant form.

High quality finishes and visual concrete, reflecting the client’s aspirations were employed throughout the building, and is the key feature internally. Extensive use of visual concrete is prevalent in the ceilings, soffits, columns, and balustrades, but is most strikingly executed in a dramatic sculptural staircase. It was also the intention to use concrete as part of a restrained material palette, both to compliment other finishes such as timber wall paneling, or to be regarded in its own right for its visual and tactile qualities.

350mm thick Thermally Active Building Slabs (TABS) are incorporated within all floors of the building, providing heating and cooling, zonally controlled to all office and library spaces. The chilled/heating pipework is connected to twenty geothermal boreholes in the adjacent landscape and supplemented by an air source heat pump. This approach enabled a “simple ceiling approach” - unfettered by mechanical and electrical systems, raising the architectural quality of the interiors.

Visual concrete or “special finishes” were used throughout the project. All elements regardless of varying compressive strengths utilised the same specification for consistency of colour and finish. This approach was also considered easier to deliver on-site. Care was given to the setting-out and detailed features, such as board jointing, flush and chamfered junctions, as well as tie-bolt locations, and formwork and falsework layouts.

The concrete frame thus is multi-functioning: structurally supporting the building, providing an elegant aesthetic, and helping to regulate the internal temperatures.

Written by Paul Mullin, Associate Director and James Kirk, Associate at MICA.

Paul led the East Ham team to deliver the Customer Service Centre and Library along with the Sixth Form Centre which grew out of a wider Civic Campus Masterplan. Paul and the team worked closely with engineers HRW, the Concrete Centre, and the concrete subcontractor Getjar to refine the specification, undertake control samples and finally to deliver the visual concrete to everyone's satisfaction. You can read more about the use of concrete in East Ham in the Concrete Quarterly:

The Naked Civic Servant, Concrete Quarterly Summer 2014

What Lies Beneath, Concrete Quarterly Summer 2015

James has been working with the existing buildings at Centre Point since 2011, working directly with the client to ensure the integrity of the original design is enhanced through the new works, re-enlivening a 1960's London icon. You can read more about working with the existing concrete at Centre Point in the Concrete Quarterly: